What’s Wrong with AI Tools and Devices Preventing COVID-19?

Addressing the pandemic with IT

Ever since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic, multiple public and private organizations across the world shut down in order to minimize the spread of the disease. As the end of the year approaches, some businesses and government offices are slowly resuming operations. These organizations are also observing safety protocols put forth by leading medical and scientific institutions, such as the WHO and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Some of the most common safety measures today include measuring a person’s temperature, covering your nose and mouth with a mask, contact tracing, disinfection, and social distancing. Many businesses have adopted various technologies, including those with artificial intelligence (AI) underneath, helping to adhere to the COVID-19 safety measures.

As an example, numerous airlines, hotels, subways, shopping malls, and other institutions are already using thermal cameras to measure an individual’s temperature before people are allowed entry. In its turn, public transport in France relies on AI-based surveillance cameras to monitor whether or not people are social-distancing or wearing masks. Another example is requiring the download of contact-tracing apps delivered by governments across the globe.

While many of these solutions help to ensure that COVID-19 prevention practices are observed, many of them have flaws or limits. In this article, we will cover some of the issues creating obstacles for fighting the pandemic.

Issue #1. Manual temperature scanning is tricky

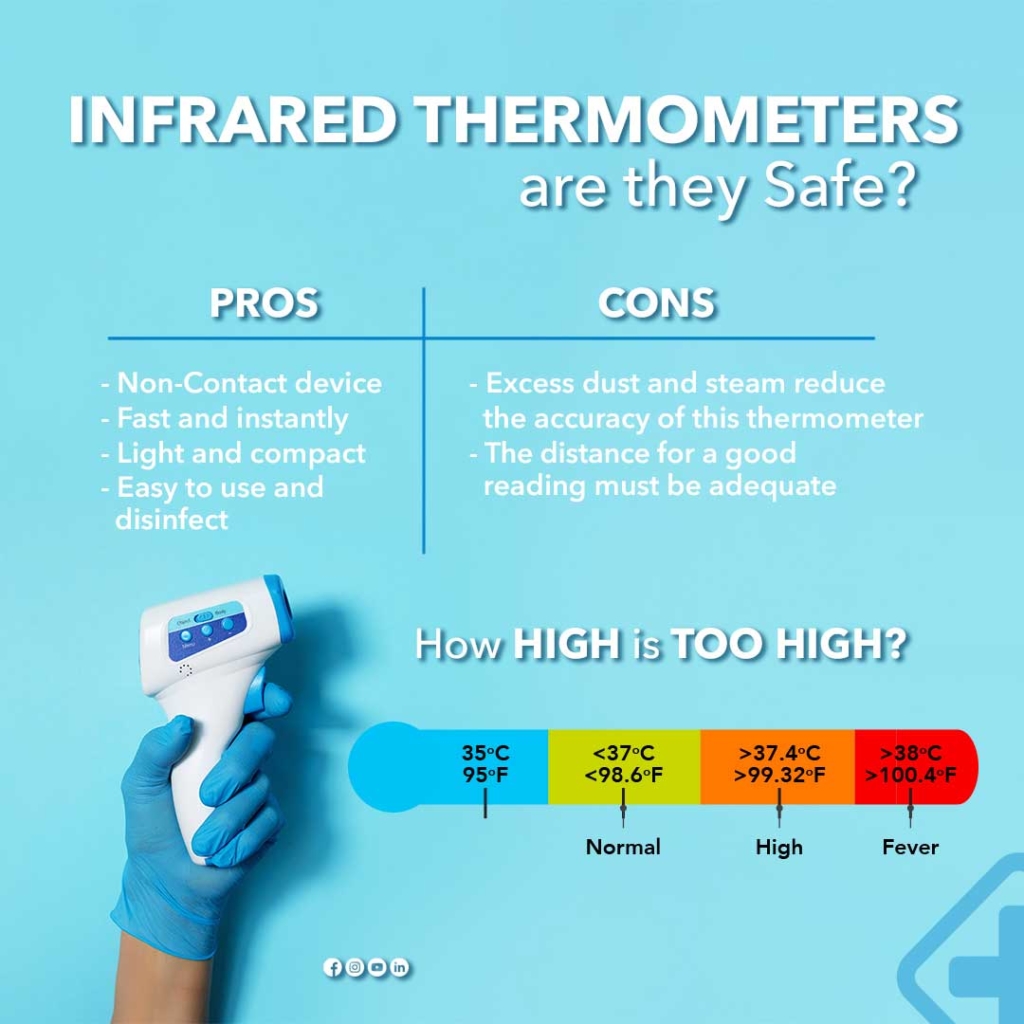

Since running a fever is one of the most common symptoms of the COVID-19 infection, most establishments now require a person to have their temperature measured before they can enter. Many businesses use noncontact temperature assessment devices to take measurements. This is usually achieved with personnel that are equipped with handheld infrared (laser) thermometers.

However, though the manual use of a single noncontact device enables businesses to quickly get a person’s temperature reading, this can generate long queues at an entry point. Besides, the use of handheld infrared thermometers still put people at risk of spreading the infection, because they are used in close proximity. There is also the added problem of handheld infrared thermometers being inaccurate and prone to human error.

Pros and cons of infrared thermometers (Image credit)

Pros and cons of infrared thermometers (Image credit)On the other hand, while thermal imaging systems can resolve the issues with handheld infrared thermometers, many of these systems lack features necessary for providing immediate responses, such as automated alerts, real-time notifications, and reporting. Neither can they monitor people flow in real time, nor track social distancing.

Many of these problems can be solved with installing mass temperature screening systems—based on machine learning techniques such as face recognition—in public places. (That’s why we introduced AI-based Fever Screener this April, helping to reduce the burden on the medical staff.)

Issue #2. Monitoring crowds is even more complex

Even with mass monitoring in place, thermal scanning solutions may not be capable of factoring in external sources of temperature, such as ambient environments or hot cups of coffee. Other issues are associated with wearing accessories, influencing the accuracy of readings.

COVID-19 primarily spreads from person to person through droplets released when coughing and sneezing. Since this is one of the most common means of transmitting the disease, governments across the world are now recommending people to wear masks in public or when around others not living in the same household. In addition to masks, most areas have social distancing measures in place to further minimize the risk of spreading the infection.

To ensure that these safety measures are maintained, many establishments make use of surveillance systems with facial recognition capabilities to monitor crowds of people in real time. However, many face recognition algorithms fail to detect a person wearing a mask, a hat, or sunglasses. According to NIST research, this is due to previous models (in the pre-COVID era) being trained on data sets of people who were not wearing masks.

Identifying incorrect face mask wearing using the SRCNet classification network (Image credit)

Identifying incorrect face mask wearing using the SRCNet classification network (Image credit)Since the beginning of the pandemic, this technical issue is being addressed by numerous machine learning projects—so far, 80+ libraries can be found on GitHub. We participated in the movement, as well, by delivering the Mask Detection solution, which was created in the course of our experiments with mass fever screening.

Issue #3. Contact tracing leads to privacy concerns

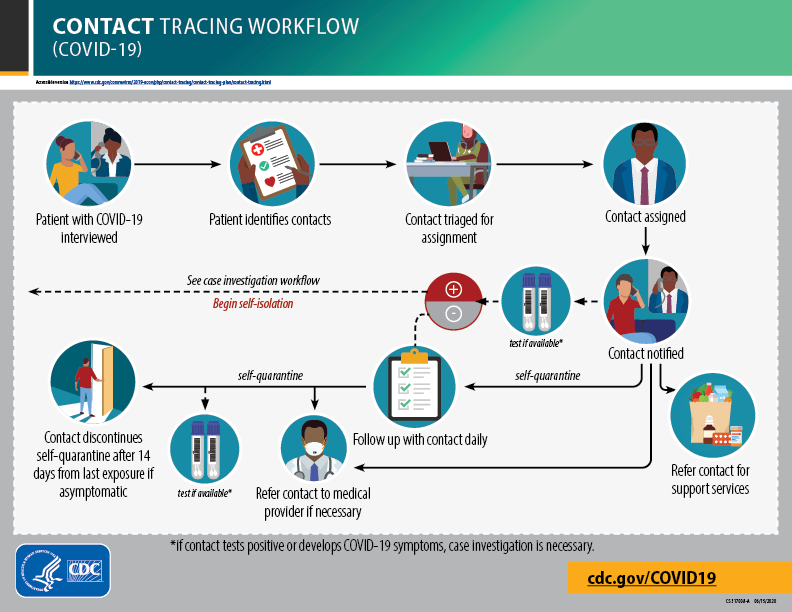

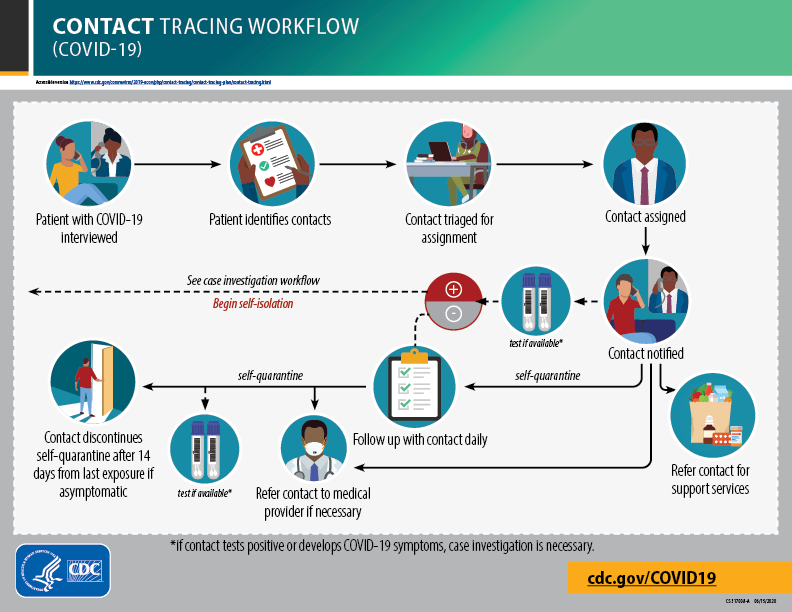

Although the CDC and the WHO have released guidelines for contact tracing, the implementation vastly differs from country to country. For instance, in most parts of Southeast Asia, contact tracing is done manually with dedicated teams conducting interviews with infected individuals. On the other hand, mobile applications are being developed in the United States and in Europe to digitize the entire contact tracing process.

The CDC’s contract tracing guide (Image credit)

The CDC’s contract tracing guide (Image credit)Regardless of the method of implementation, contact tracing itself may lead to serious privacy violations. This is especially true for the United States and Europe, where regulations such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) are enforced.

Despite existing privacy regulations, governments all over the world have already developed their own contact tracing apps: Corona-Warn-App in Germany, COVIDSafe in Australia, and TraceTogether in Singapore, ProteGO Safe in Poland, etc. The governments are looking for some kind of a compromise between monitoring and privacy, tracking only those who gives a clear consent, while users are expecting that data usage is as transparent as possible. While many of these apps prioritize safety and are efficient for finding unreported COVID contacts, the issue of privacy is still an ongoing discussion.

Issue #4. UV rays harm eyes and skin

While COVID-19 primarily spreads from person to person, it is also possible for an individual to get infected when they touch contaminated surfaces and then touch their face. Because of this, it is very important to maintain regular cleaning and disinfecting procedures, especially in hospitals and other high foot traffic locations.

In order to preserve a safe level of cleanliness at all times, many establishments now maintain multiple cleaning and disinfecting routines daily. In the past few months, the constant need for disinfection has made ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI), a method that uses short wavelength ultraviolet (UVC) light, very popular.

Previous studies have shown that UVC light can be used to treat the SARS coronavirus. While UVC light can certainly destroy microorganisms, the scientific community has not yet concluded a specific dosage needed for COVID-19. One particular study noted that COVID-19 had the highest UVC dosage needed for deactivation among nearly 130 viruses.

Although UVC lights can destroy traces of COVID-19, exposure to it without proper equipment is dangerous for human beings. While in some buildings disinfection can be made at nights when people leave, a number of questions arise for businesses, employees, visitors, and cleaning staff working 24/7. How do cleaners know when to enter a room for cleaning? How do visitors or tourists know when to enter a room? How do people know whether a room has already been disinfected? How can lamps be switched off lamps safely? In this case, a strict cleaning schedule, as well as safety measures and automation, must be introduced.

For instance, Altoros equipped its UVC disinfection lamps with motion sensors and smart plugs, preventing any potential accidents by switching off when someone enters a room. (The same goes for our UVC Robots distinguishing humans from objects.)

Issue #5. UVC robots are extremely expensive

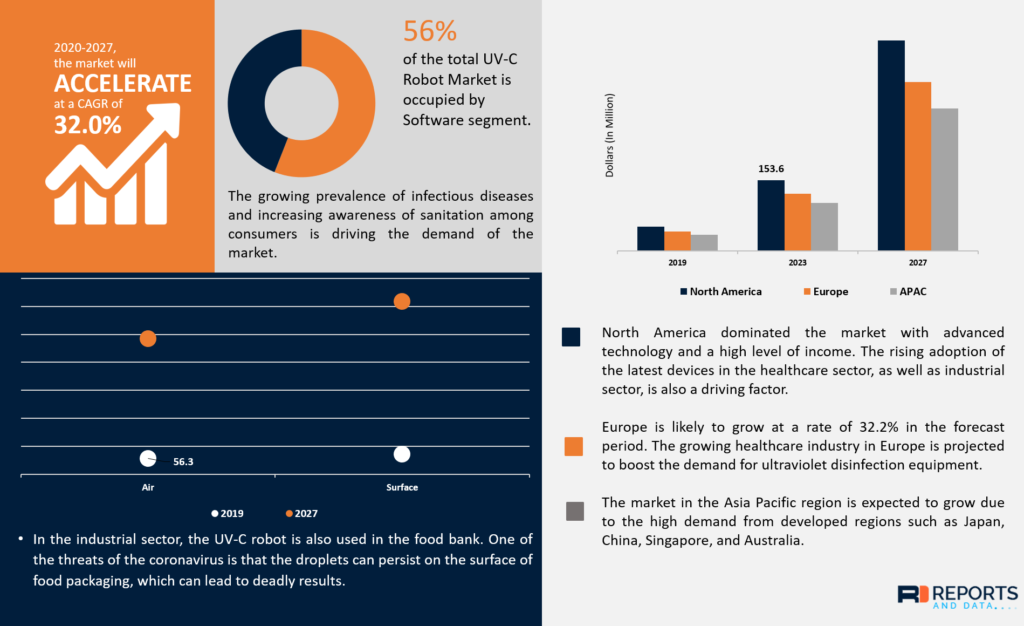

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, the UVC robot market was already predicted to increase from $171.8 million in 2019 to $1.46 billion in 2027. Now, with the ongoing pandemic, the demand for UVC robots has surged up, increasing how much each of these devices costs.

To get an idea of how much UVC robots cost right now, the Mobile Robot Guide recently released a special report featuring autonomous solutions for COVID-19. According to their report, the average price of a UVC robot is $53,000, while the most expensive cost $125,000. With the heightened demand for UVC lights, these prices can be expected to increase.

Given how expensive UVC robots cost on average, the majority of organizations will not have the resources necessary to acquire one. This can also be an issue for many developing regions. Hospitals, where these UVC robots will be essential, may have to forego other critical expenses just to have the budget. As a consequence, working with customers, we noticed that most of them are more likely to buy more affordable COVID-19 prevention alternatives: AI-based fever screeners or automated UV-disinfection stations (integrated with smart plugs), rather than robots.

The expected growth of the UVC robot market by 32% from 2020 to 2027 (Image credit)

The expected growth of the UVC robot market by 32% from 2020 to 2027 (Image credit)Even if resources were not an issue, ordering these devices is a challenge in itself, as deliveries can take months due to the high demand for UV lamps and other robotic parts. Additional shipping delays can also be attributed to the closure or heavy restrictions of some borders. When contacting manufacturers of robot parts this summer, our engineering team faced the situations like that—many of the suppliers were not able to cope with the growing amount of orders.

One of the recent initiatives to address this was UV Robot Design Contest by Micron Technology held from June to September this year, aiming at delivering a robot for less than $10,000.

Issue #6. No integration, no compliance, no transparency

While a particular business may be using one or more solutions previously mentioned, it is probable that some of the technologies were not designed to be integrated or compliant. For instance, some of the technologies or devices utilized in preventing COVID-19 may not meet security requirements (e.g., for their cloud storage) or lack an API. The questions related to HIPAA, HITECH, or GDPR may arise.

An average enterprise has hundreds or even thousands of apps in use, which may also lead to additional development efforts, customization, security measures, and system integration. In this case, an organization should be ready for associated “hidden costs” and plan beforehand.

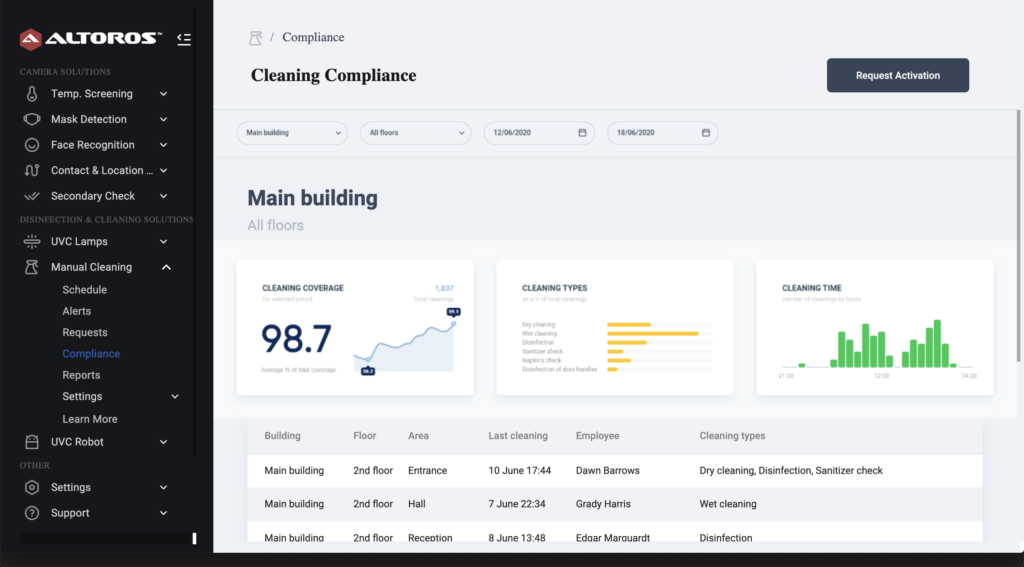

The lack of integration capabilities (such as an API) can result in another problem: the lack of required transparency and gaps in reporting. In addition, what about notifications and history of monitoring/disinfection? While a facility’s employees or hotel administration can be aware of the full picture to some extent, what about the visitors? How to tell them that the building is safe enough and was recently disinfected?

This was one on the reasons we delivered the Alarta safety platform and introduced real-time disinfection status reports available for both facility administration and guests. E.g., the cleaning module generates QR codes that can be printed out and attached to lodging doors, providing cleaners and visitors with detailed information on the status of disinfection. This way, before entering a room, a person may know how and when the it was last disinfected, what is the schedule for the next cleanups, etc.

A sample cleaning/disinfection report for Alarta managers

A sample cleaning/disinfection report for Alarta managersRegardless of the safety measures in place and existing issues, innovations are already playing a vital role in the fight against COVID-19. By improving on existing technology, we can make everyone safer as we all adjust to the new normal.

Further reading

- The Pitfalls of Creating Appointment Scheduling Apps for Healthcare

- Cross-Modal Machine Learning as a Way to Prevent Improper Pathology Diagnostics

- Experimenting with Deep Neural Networks for X-Ray Image Segmentation

with assistance from Sophia Turol.