Hyperledger Incubation: Burrow Integrates Ethereum Virtual Machine

Complementary, not competitive

“Any positioning of the Hyperledger and Ethereum communities as competitive is incorrect,” wrote Hyperledger Project Executive Director Brian Behlendorf recently. He made his comment against the backdrop of the Hyperledger Technical Steering Committee’s (TSC) recent approval to incubate the Burrow project, a joint proposal from Monax and Intel.

Burrow, formerly known as ErisDB, is described as a permissionable smart contract machine. “It provides a modular blockchain client with a permissioned smart contract interpreter built in part to the specification of the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM),” according to Monax CEO Casey Kuhlman.

Casey backed up Brian’s view when Monax joined the new Enterprise Ethereum Alliance. He also submitted the incubation proposal for what would become Burrow into the Hyperledger Project. “Are these (two actions) competitive? Not in our view,” he wrote at the time.

Brian referred to the Burrow incubation as “another important milestone in the Hyperledger books.” Indeed, the Hyperledger Project has proved to be fecund since its creation in December 2015, with several incubations now competing for community involvement and mindshare.

So, let’s burrow into Burrow.

The importance of smart contracts

Specifically, Burrow brings the promise of smart contracts to the front and center of the conversation. Smart contracts are seen as the killer app for permissioned enterprise blockchains (a.k.a. private blockchains, distinguished from their public counterparts by a lack of a cryptocurrency and lack of anonymity among users). They promise to bring a new era of transparency, immutability, and efficiency to the core database and ledger that forms the heart of blockchains.

“The blockchain community still has many technical challenges to solve, and many different possible approaches to solving them. ‘Permissioned’ and ‘unpermissioned’ (networks) represent two ends of a range of options for configuring a distributed ledger, not a binary choice.” —Brian Behlendorf, the Hyperledger Project

The Burrow project has been open-sourced since December 2014—previously, it was a part of the Eris blockchain platform from Monax. It was originally licensed under GPL3, but has now left the copyleft world and been re-licensed to Apache Software License 2.0, “in accordance with Hyperledger governance requirements,” according to Brian.

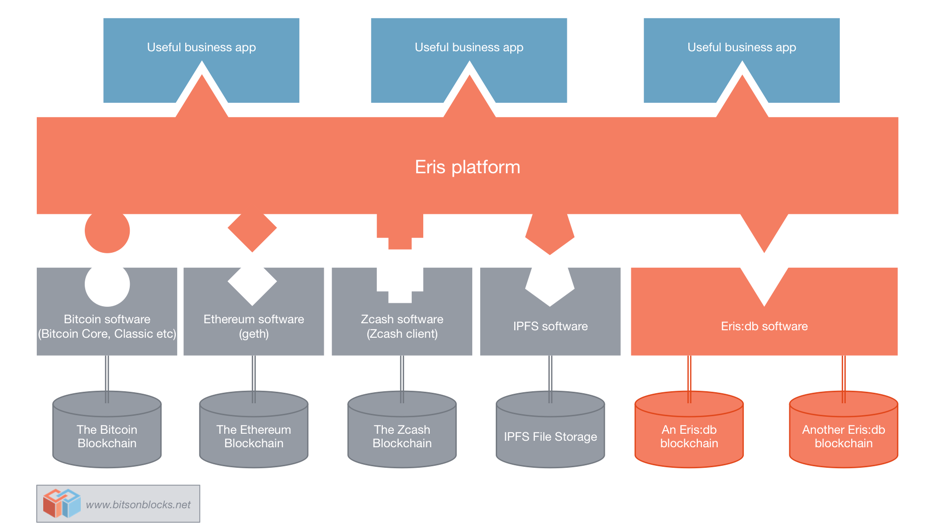

ErisDB within the Monax platform stack (Source)

ErisDB within the Monax platform stack (Source)Beyond that, these are still the very early days of blockchain, as Brian acknowledged recently.

He also stated that “choices we can make at the smart contract layer are even more complex. Being able to collaborate on various approaches to these problems is fundamentally important to getting really innovative ideas into production-quality code as quickly as possible.” Brian cited a new-found ability to “experiment with integrating the EVM” into other Hyperledger distributed ledger incubations (e.g., Fabric, Sawtooth Lake, and Iroha).

“Burrow’s architecture opens up a range of interesting cross-project collaborations.”

—Casey Kuhlman, Monax

Casey seconds that thought, noting that Burrow provides “a strongly deterministic smart contract focused on blockchain design to the Hyperledger Project’s overall effort,” he wrote. “Burrow’s architecture opens a range of interesting cross-project collaborations within the Hyperledger umbrella.”

It’s also important to note that “Monax’s permissioned EVM is functionally separate from the Ethereum protocol or any of the codebases implementing it,” according to Casey. “Burrow’s users can operate any smart contract that has been compiled by any EVM language compiler in their own permissioned blockchain environments.”

How it works

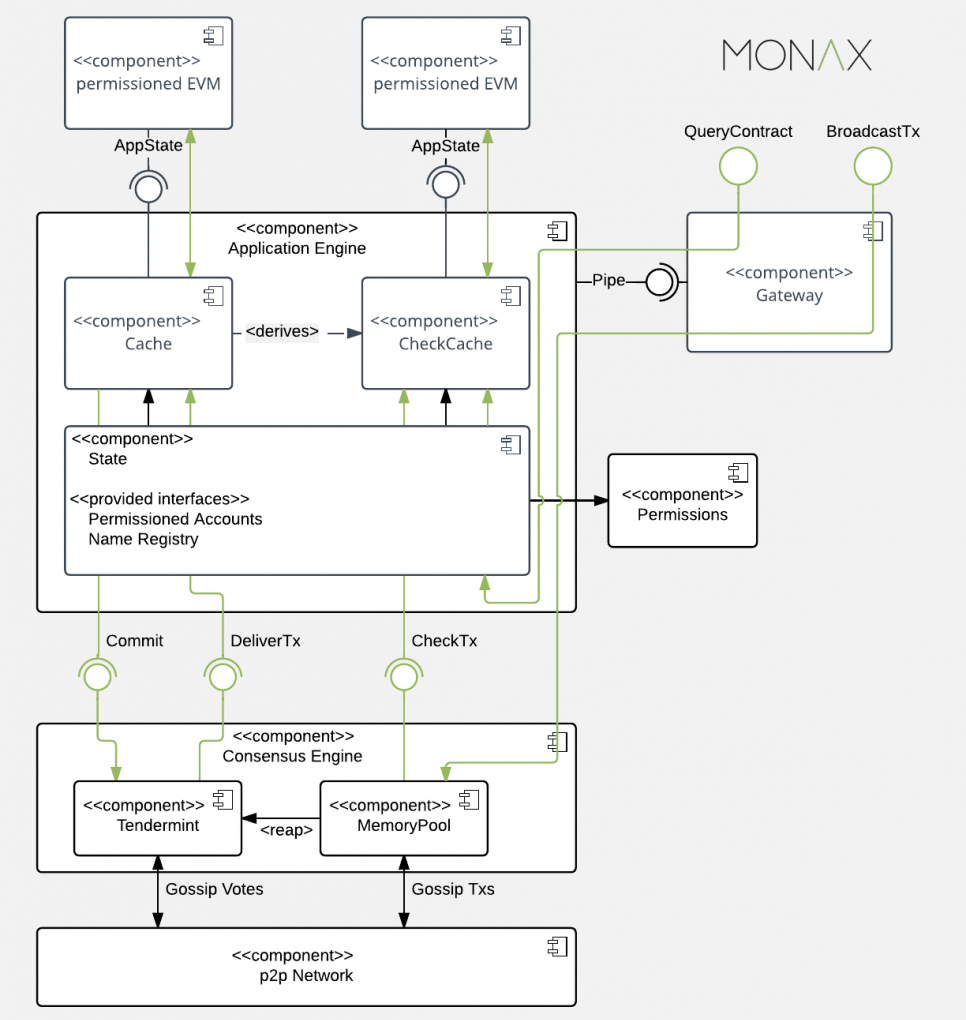

A high-level graphic of the Burrow architecture looks like this:

Source

SourceIts major components include:

- Consensus engine responsible for maintaining the networking stack between nodes and ordering transactions to be utilized by the application engine.

- Application Blockchain Interface (ABCI) provides the interface specification for the consensus engine and application engine to connect.

- Smart contract application engine provides application builders with a strongly deterministic smart contract engine for operating complex industrial processes.

- Gateway provides programmatic interfaces for system integrations and user interfaces.

- Permissioned Ethereum Virtual Machine, built to observe the Ethereum operation code specification, additionally asserts the correct permissions have been granted. Permissioning is enforced through secure native functions and underlies all smart contracts.

- Application Binary Interface (ABI). Transactions need to be formulated in a binary format that can be processed by the blockchain node. Future work on the light client will be aware of the ABI to natively translate calls on the API into signed transactions that can be broadcast on the network.

- Cryptographically Secured Consensus. The proof-of-stake Tendermint protocol achieves consensus over a known set of validators, where every block is closed with cryptographic signatures from a majority of validators only.

- Remote signing. Burrow accepts client-side formulated/signed transactions for which it has an interface for remote signing available, allowing blockchain nodes to be ran on commodity hardware. Work continues to enable remote signing for the validator block signatures, too.

- Multi-chain universe conceived for orchestrating many chains, as exemplified by the command “monax chains make” or by the fact that transactions are only valid on the intended chain.

Consensus and validation are ever-present in discussions of the blockchain technology. With Burrow, Manox and Intel have gone with the TendermintCore consensus engine, which runs Byzantine Fault Tolerance consensus. This method is touted for its flexibility and performance in the relatively high-throughput networks in which it is expected to be used. It can be scaled to encompass “hundreds or thousands of validators,” according to its backers.

A technical dive into the components can be found in Borrow’s GitHub repo or this comparison.

Standardizing interfaces

Burrow uses boot and runtime interfaces, and its curators write that “we’d be very interested in working across the other Hyperledger projects to come to agreement on the following interfaces:

- genesis.json (or equivalent network state at boot file) specification

- config.toml (or equivalent node runtime file) specification

- high-level RPC | API | Gateway interface specification”

While various blockchain clients will differ in their RPC, the project’s sponsors believe that much information can and should be standardized. As they also wrote, “it is our view that as much standardization as possible for those interfaces across the various Hyperledger blockchain engines would greatly benefit developer tooling, developer operations systems, and blockchain explorers.”

The Ethereum and Hyperledger tango

Still, the statements about collaboration and integation won’t keep enterprises from evaluating Hyperledger and Ethereum on an either/or basis, as well, so one wonders whether the best historical analogy would be AC versus DC current, General Motors versus Ford, or Microsoft versus Apple.

The first of these had a clear winner and loser (when Westinghouse’s AC grid triumphed over Edison’s DC dream), the second helped create a massive automotive industry with many competitors, who all create a highly standardized product, and the third helped to create a huge software industry that’s still fraught with incompatibility.

Or maybe there is not a good historical analogy. Searching for a suitable one, this may be an irrelevant quest. One distinctive thing about the beginnings of this blockchain era is the continued focus on open-source projects.

Even with the perhaps-not-so-altruistic presence of industry heavyweights, such as IBM and Intel in the Hyperledger world, and very large financial institutions throughout the blockchain world, these projects remain driven by communities, committees, and a certain earnestness among developers that’s been ubiquitous from the start in the open-source movement. The idea is you can go through an analytical process without getting trapped into a new era of vendor lock-in.

Whether working for a cool fintech startup or a somber Global 2,000 behemoth, enterprise IT decision-makers will be required to go through their analytical processes, no matter how non-competitive the specific blockchain movements claim to be. However, with open source, the idea is they can do so without getting trapped into a new era of vendor lock-in.

They can also contribute. Anyone is free to join in, participate in meetings and on committees, and write code to drive things forward. There are no secret handshakes or hazing involved.

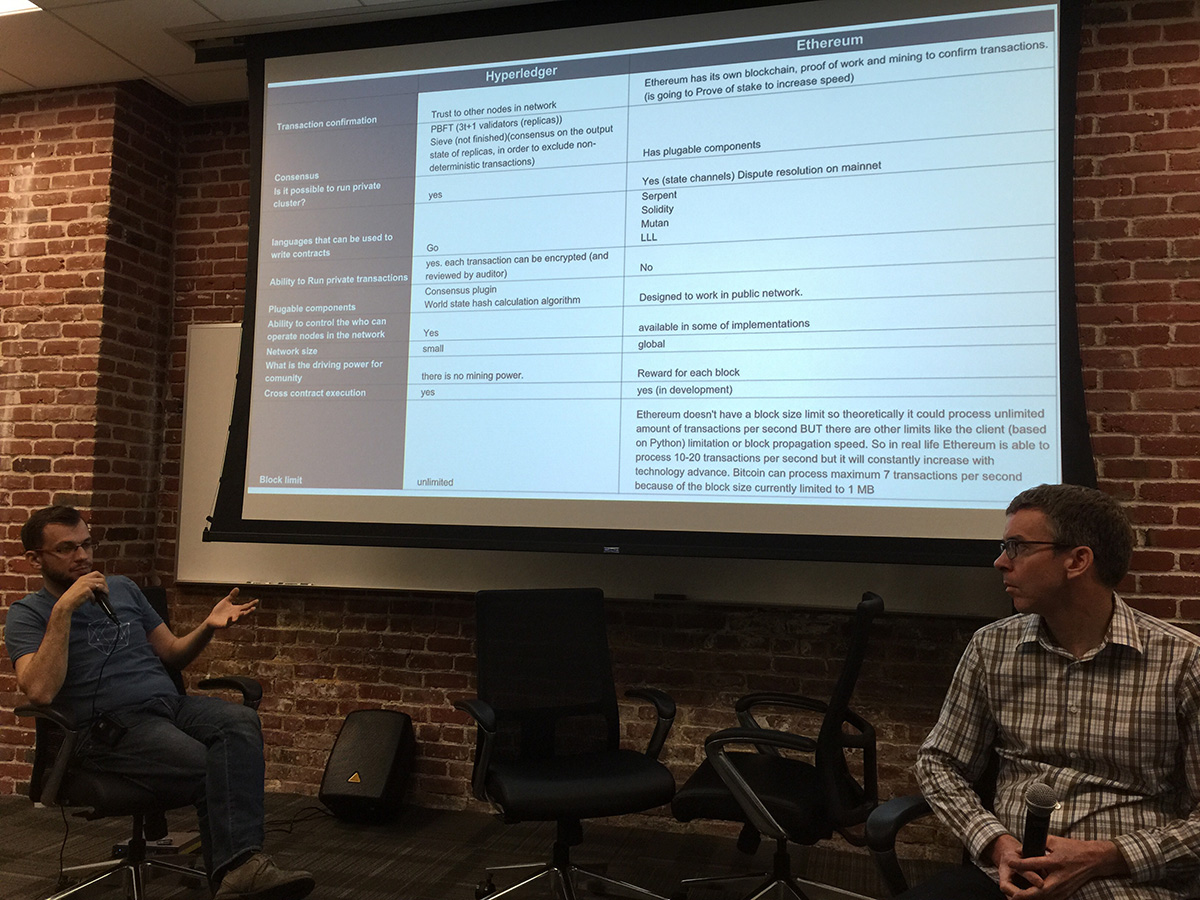

Hyperledger vs. Ethereum? (A panel on the topic)

Hyperledger vs. Ethereum? (A panel on the topic)The lack of big enterprise customers in helping to shape much of today’s emerging technology is a concern I’ve heard expressed within more than one community. So, many technology vendors today are exposing many of their secrets and their people to their competitors, in a spirit of a rising tide that will lift all boots. It’s frustrating to see technology customers remain standoffish, presumably through fear of revealing their intellectual property (a.k.a. secrets).

The worldwide blockchain communities, to be fair, have shown some notable exceptions, as large financial institutions warily approach one another in the spirit of disintermediation, efficiency, and fear of getting “Ubered.”

Thus for now, we can accept the efforts of Brian, Casey, and many others, who proclaim loudly and clearly that they are offering great choices for potential blockchain customers, not a group of walled gardens. Seeing Ethereum and Hyperledger tango with one another should offer inspiration for us all.

Related reading

- Hyperledger vs. Ethereum: Yes? No? Maybe?

- The Ethereum Blockchain Platform Enters the Hyperledger Picture

- Hyperledger Meets Ethereum: Integration and the Future

Hyperledger incubation

- Hyperledger’s Sawtooth Lake Aims at a Thousand Transactions per Second

- The Iroha Project to Bring Mobility to Blockchain with Simple APIs

- Hyperledger Fabric v1.0: Multi-Ledgers, Multi-Channels, and Node.js SDK