Cloud Foundry Summit Sessions: How Diego Reenvisions the Elastic Runtime

At this year’s CF Summit, Onsi Fakhouri of Pivotal delivered an amazing session on Diego highlighting why it is important for Cloud Foundry developers and how it will evolve in the future.

Diego, a large-scale project, which Pivotal is currently working on, will introduce a number of significant changes to the Cloud Foundry architecture. This blog post shares why we should care about Diego, what impact it will have on Cloud Foundry and PaaS, and the reasons for reenvisioning the runtime.

Why was the Elastic Runtime rewritten?

Diego is an almost complete re-write of Cloud Foundry Elastic Runtime. This includes a large part of the system, the entire DEA Pool, together with Warden, the Health Manager, NATS, etc.

The need to invest into this kind of endeavor came due to multiple drawbacks of the existing architecture:

- issues with orchestration

- poor separation of concerns

- triangular dependencies

- tightly coupled components

- limitations of Ruby

- domain specificity

- platform specificity

As a result, it is hard for developers to add new features and maintain existing ones, hard to test, and hard to understand how the system works. Onsi Fakhouri illustrated these challenges with several real-life examples:

- Since the Cloud Controller is responsible for too many things, it may be inefficient when deciding how to distribute apps across DEAs. This causes orchestration issues.

- The Cloud Controller, Health Manager, and DEA Pool were designed to work together and are tightly coupled. Due to this, adding new features to the Cloud Controller may negatively affect the Health Manager and/or the DEA Pool.

- Domain and platform specificity make it difficult for developers to extend the system.

- Finally, DEA and Warden (two long-lived, long-running processes) have lots of concurrency and low-level OS interactions. As a result, the Ruby code currently used by the system has been pushed to the limit.

How is Diego different?

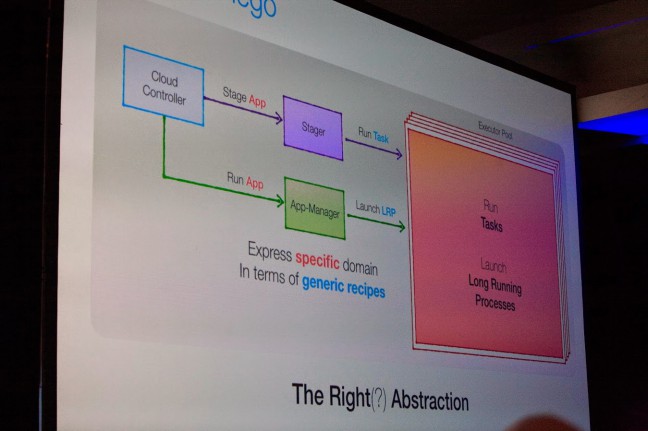

Diego aims to provide the right level of abstraction that will make it possible to overcome the above-mentioned challenges and make Cloud Foundry more robust.

Unlike the current Elastic Runtime, Diego is written in Go. The project has both powerful concurrency and low-level OS support, while being strongly typed. Then, Diego provides explicit error handling and promotes developer discipline (the Go language requires better developer discipline than Ruby).

What does it mean to developers?

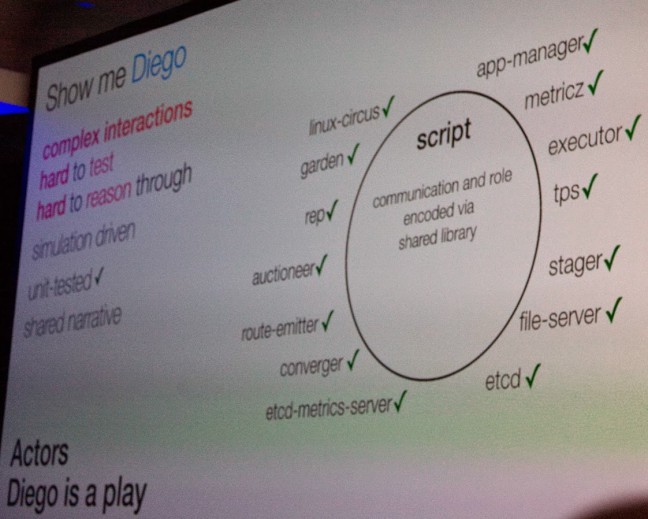

Diego embraces the complexity, necessary in a platform like Cloud Foundry, and tries to make it explicit, transparent, and understandable. Thanks to this, it is easier for developers to work with the system, add and test new features, maintain existing ones, etc. Onsi Fakhouri used some examples to illustrate this.

As we have already said above, Diego is written in Go, a programming language developed in the cloud era. It eliminates many issues caused by Ruby.

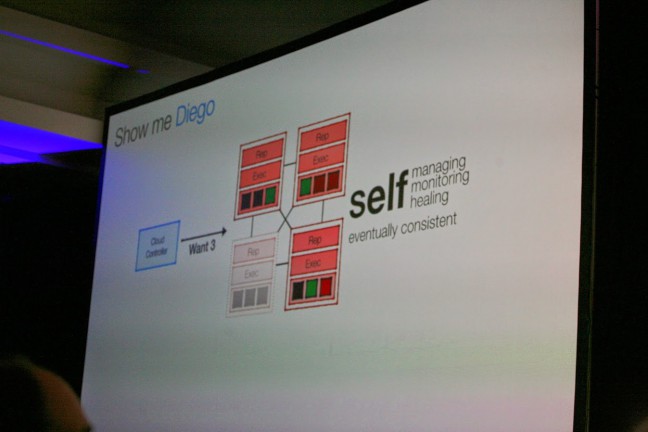

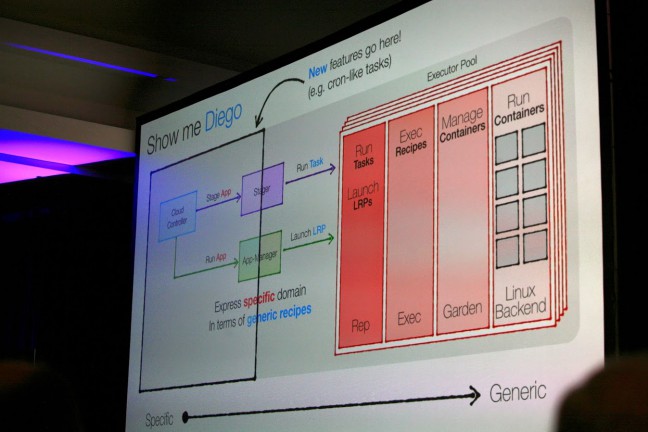

Diego still has the Cloud Controller, but the DEA Pool has been replaced with the Executor Pool, an eventually consistent, self-managing, monitoring, and healing system. As a result, Cloud Foundry becomes more robust, and the Health Manager is no longer necessary.

Diego solves the domain specificity issue by replacing complex notions, such as running apps, with generic ones, such as one-off tasks (one-time jobs) and long-running processes (LRPs). As a result, adding new features becomes easy.

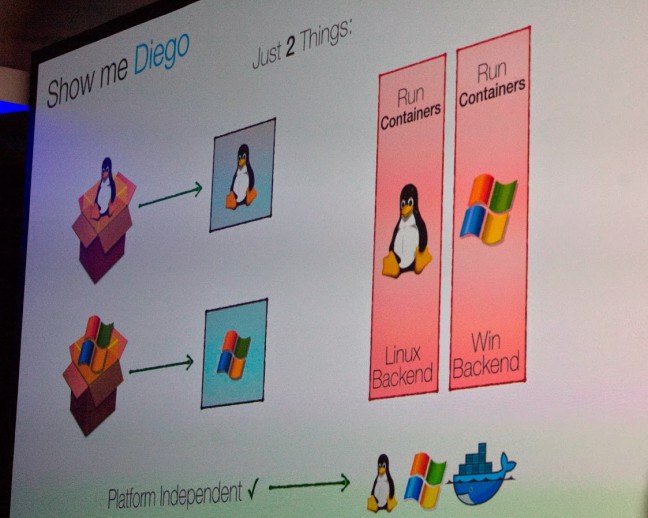

Diego has been built from ground up to be platform-agnostic. Most of the components, including the Cloud Controller and the layers in the Executor Pool, except for the back-end layer, do not care about the platform. This means, when adding a new platform, developers only need to care about two things: the backend and the binary for that specific platform.

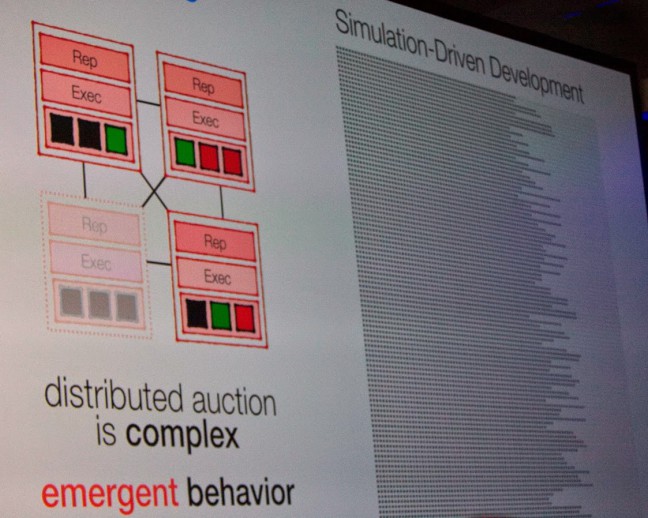

Removing part of responsibilities from the Cloud Controller has solved the orchestration issues. The Cloud Controller does not have to think about how and where the apps will run any more. Instead, the Executor distributes long-running processes using the auction method.

In total, there are 14 different components, each responsible for a single separate job. It creates a lot of complexity, which is inherent to large-scale systems, such as Cloud Foundry. This is why Pivotal uses the simulation-driven approach when working on Diego. During the session, Onsi Fakhouri demonstrated how it evenly distributes 1,000 apps across dozens of executors, using a piece of the same code that runs in production.

Unit testing is done on all components to ensure that each of them operates as expected. In addition, a special library provides shared narrative and integration tests to make sure everything works as it should.

Current situation and a roadmap for Diego

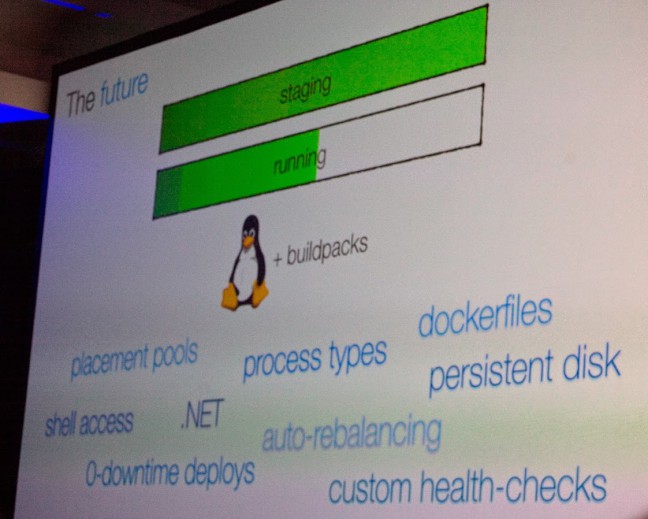

By now, the team has completed work on the staging components. The part responsible for running apps is half-done. There is already support for Linux and buildpacks.

The list of the features that will be included into the project is a long one. According to Onsi Fakhouri, soon Diego will provide placement pools, process types, persistent disk, shell access, autorebalancing, zero-downtime deploys, support for Doecker files, .NET support, and custom health checks.

To sum it up, we may describe the Diego project as Elastic Runtime 2.0. The things that make it different from the one employed in Cloud Foundry today are as follows:

- It uses the notions of tasks and LRPs to provide flexible abstraction.

- It is platform-agnostic and, therefore, extensible.

- It is self-managing, -monitoring, and -healing, making Cloud Foundry more robust.

- It embraces complexity.

Let’s see how Diego will evolve to bring even more positive impact to the PaaS.

Further reading

- How to Push Private Docker Images and Enable Caching on Cloud Foundry Diego

- .NET on Pivotal Cloud Foundry: Scaling an App on Diego

- Cloud Foundry Advisory Board Meeting, July 2016: Time to Migrate to Diego